This month, the Eponaquest News will share thought provoking excerpts from the revised and expanded edition of Linda Kohanov’s highly influential book The Tao of Equus. The new edition will be published in June 2024, but you can get an in-depth look at how this now classic book (originally published in 2001) brings together mind and heart expanding insights into the transformational power of the horse-human bond. In the following excerpt from “Chapter Four: Mind Under Matter,” Linda turns conventional ideas about human and animal intelligence inside out and upside down as she shares what it was like to see herself through the eyes of a horse, and how her life changed as she adopted this expansive perspective, not only in working with horses, but in redefining her perspective on humanity’s dysfunctional perceptions and untapped potential.

In the next edition of the Eponaquest News, Linda will share part 2 of this chapter, offering insights into how standard metaphors of light and dark limited humanity’s understanding of consciousness and led our ancestors down an unnecessarily destructive path. She also brings in key theories and studies that help explain the power of equine-facilitated learning and therapy that weren’t available when the original version of The Tao of Equus was written in the late-1990s. In the meantime, Linda is celebrating the release of the revised book by offering 20 percent off her upcoming four-day equine facilitated workshop “The Tao of Equus 2023” in October. See the end of this newsletter for more information.

Chapter Four

Mind Under Matter

(Part 1)

With strip malls and subdivisions devouring its desert outskirts, Tucson is no longer the Wild West by any stretch of the imagination. There is, however, one saving grace: an intricate network of washes that meander through the foothills and down into town like nature’s own veins and arteries staking a claim for her survival. Most of the year, these snakelike passageways of mesquite, creosote, and cactus are dry, offering sanctuary to a healthy population of coyotes, javelinas, lizards, tarantulas, and rattlers. Yet during the monsoons of late summer, you can predict the severity of a distant storm by how fast the water rises through the floodplains in your neighborhood while the sun still shines overhead.

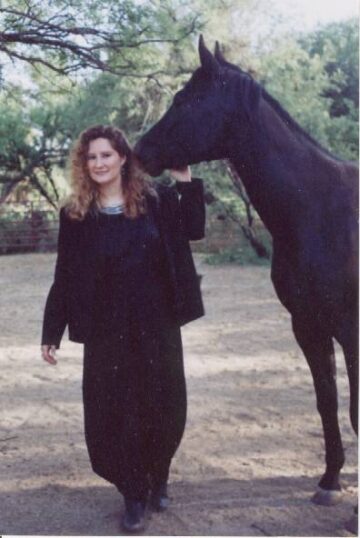

For Tucson’s large population of amateur equestrians, these washes provide the last vestige of fenceless desert suitable for rides long enough to warrant saddlebags. Somehow, it’s comforting to know that the moment civilization proves too much to bear, I can tack up my horses, and without crossing any major roads, head for the hills, perhaps never to be heard from again. There were, in fact, two years when I was as good as gone, though I managed to limit most of my excursions to the washes within a five-mile radius of my home. By chance, I happened upon an oasis in the desert, a small private ranch where I boarded my horses Rasa and Noche in the mid-1990s. Nestled in a mesquite grove, this ten-acre plot of desert heaven provided instant access to an extensive maze of washes and undeveloped land just minutes from my house. There I developed the courage to conduct my unconventional inquiries into horse-human relationships. I suspect that by the time I finally moved my herd to a facility better suited to training and teaching, the people who lived around that secluded little ranch were not at all convinced of my sanity.

My activities appeared innocent enough at first. I’d saddle up Rasa with provisions to last the day, and we wouldn’t be seen again until dark — sometimes well after dark if the moon was full. Together we’d explore some undeveloped stretch of desert, but it wasn’t really the riding that intrigued me. After all the time I had spent on the ground with Rasa during her time of convalescence from a serious injury, I found that I often preferred walking beside her even when she showed no signs of lameness. The fact that she could carry water and lunch for us both, not to mention a few drinks, a blanket, and some writing supplies made it worth tacking her up, of course, but we both were more interested in finding some shade and a good patch of grass than logging serious miles on the trail.

Something shifted in me during those lazy afternoons. The black horse and I began to move and breathe in sync, to wander across the sweltering cactus forests, through the washes, and into the grass-lined mesquite groves by virtue of a flowing, give-and-take decision-making process, a form of shared leadership best described by the most basic meaning of the word consensus: “to sense together.” One day, this full-bodied, dual mode of perception blossomed into something even more intimate.

We were wandering through a field dotted with scrub brush, palo verde trees, and cholla cactus. Rasa was sauntering along, muzzle to the ground, sniffing casually at old sticks, snatches of coyote dung, and tufts of dried wildflowers. When she discovered a sizeable clump of grass, I had nothing to do but prop myself against a rock and wait for her to devour every last blade. I reached over, absentmindedly picked a creosote blossom and held it to my nose. A chorus of mesquites swayed to the music of heat waves. The Catalina Mountains loomed over the valley a good four-hour walk away. My thoughts expanded to fill the distance and eventually evaporated all together.

Then out of the corner of my eye, I noticed the black horse gazing at me with a quizzical expression as a series of decidedly nonhuman notions began to seep into my mind. I wasn’t quite seeing through Rasa’s eyes, but almost. There were no voices buzzing through my head, no visions parading by on strings of words. It was more like an explosion of subtle perceptions dissipating into a whisper. Sight, sound, smell, and touch seemed to merge and become interchangeable. I took a deep breath. The sensations coursing through my bloodstream filled my brain and were exhaled as conscious thought. I realized why Rasa was so perplexed. After years of traveling together in so many ways, the black horse had finally noticed I was handicapped.

Not that she felt sorry for me. She merely realized we were different in ways that give her certain advantages in life, and she was sizing up how I had adapted to the challenge. My nose, which by human standards is generous enough, looked completely insignificant to the black horse. It seemed to be the root of all my problems. The fact that my neck was little more than a pedestal for my head only made matters worse — as did the placement of my ears, which were small and completely immobile, and my eyes, which only paid attention to whatever was directly ahead.

The curious mare stepped away from the grass to lick my hand, touch her nose to my own, and brush her soft muzzle against my cheek. Once again, I was flooded with a barrage of sense images. I had never before noticed how much pleasure and satisfaction horses derive from touching, tasting, and smelling simultaneously. When Rasa approaches an interesting rock or an unusual tree, she reaches out with her swan-like neck and inhales a kaleidoscope of perfumed realizations as she rubs her nostrils and sometimes even her tongue across the object. At the same time, her ears move independently, like little radars scanning her surroundings for any signs of intrigue or danger.

From the perspective we shared at that pivotal moment, it seemed my front hooves had mutated into flexible appendages designed to pick things up off the ground and hold them to my nose. To Rasa, this was my most outstanding feature, though I got the impression it would be even better if my fingers had some sort of olfactory capabilities, for my sense of smell obviously wasn’t nearly as refined as hers no matter how close I got to what I was investigating. With my front legs constantly moving through the air, bringing things to my face and carrying them around, I had essentially relinquished another sense she finds useful. Tabula Rasa knows something’s up long before she can see or smell the specifics. The pockets of air in the hollows of her hooves accentuate vibrations traveling along the ground. Unexpected visitors have a harder time sneaking up on someone who has amplifiers in her feet.

The eyes of the horse are truly amazing. Placed on the sides of her head, they’re larger than those of an elephant or whale and twice as big as my own. In certain positions, Rasa can see 340 of the 360 degrees around her, with two thin blind spots, one immediately ahead and one directly behind. Of course, this means that things look rather flat to her, and occasionally she’ll even bump her nose on something right in front of her face, but if she really concentrates, she can muster a narrow band of three-dimensional vision by positioning her nose perpendicular to the ground and directing both eyes forward.

For the remainder of the afternoon, I hovered between Rasa’s point of view and my own. I must have stared at my hands for ten minutes, marveling at their strange construction. When we hit the trail again, I couldn’t help wondering if our unusually dexterous appendages are an innovation or merely a magnificent compensation awarded to an entire species of idiot savants. I’m limited to getting around on two legs as a result, which makes it necessary for Rasa to either carry me on her back or leave me in the dust whenever a quick getaway is in order. I obviously can’t hear or smell as well as she can, but it’s difficult to imagine just what I’m missing. Consequently, it’s Rasa’s ability to see two wholly different ways that continues to impress me the most.

Human vision is great for focusing on a specific object and useful for analyzing all those things we like to make with our hands, including microscopes, pens, typewriters, and computers, which allow us to translate our observations into words to share with people we may never meet. But there is a trade-off. I can only see straight ahead, and while I can do that more clearly than Rasa, it would help to switch to that magnificent wide view of hers when I’m out in the world. Walking through the pasture with three or four feisty horses on the first cool day of autumn, I have to keep turning my head from side to side, making sure no one is about to run over me, hoping all the while that during those quick backward glances I’m not about to step into a hole or run into a fence. And what woman hasn’t experienced the creeping sensation of traversing a lonely city street, wishing she could see who belongs to those vague footsteps trailing behind her?

By equine standards, human beings wander through life virtually oblivious to their surroundings, their brains sweating in a panic as they try to dissect little bits and pieces of information in a constant struggle to fill the colossal gaps of their perception. Yet this process only distracts them further, for as they deconstruct, classify, and mull over the details of one observation, they miss everything else going on around them. The senses become that much duller in city dwellers who insulate themselves from the natural world, relying on gadgets, habits, and secondhand information to tell them how to respond to every situation — as long as it remains in an urban context. Steve and I once took a musician and his wife out to see a sacred petroglyph site so far off the beaten path there were no signs to distinguish one dirt road from another. When we arrived, the man’s wife, who was born, raised, and lived in New York City, literally short-circuited among those wide-open spaces. She refused to venture outside her hotel for the rest of their trip.

The day I became a horse for a few hours, I understood in a flash why two-legged creatures need so many statistics and experts to tell them what to do. The human herd actually encourages its members to dissociate from the body, the instincts, and the senses. Children are taught to narrow their attention, cling to the past, and focus on the future, thus losing their ability to fully function in the present. They become dependent on authority figures who themselves only excel in highly specialized environments and situations.

Tabula Rasa, of course, never encouraged me to change my ways. The world was too vast and intriguing at every moment for my apparent lack of interest to disturb her. She merely noticed my dilemma one day as if she were sizing up an old cow skull lying next to the trail. Yet once I saw myself in her eyes, I became disturbed by this uniquely human tendency to experience life as a series of overprocessed sound bites. The idea of constantly editing snippets of sensation and tapes of secondhand observation into extended works of thought lost its appeal for me that afternoon, and it took me months to reconcile my identity as a writer with the lessons I learned from my horse.

Secret Springs

There is a pool in the heart of the desert. The surface is as quiet as glass, though its waters are nourished by a mountain stream rushing endlessly underground. When the sun speaks in tongues and chases the clouds away for months, rivers turn to dust, dry grasses hiss tributes to the wind, eagles perch wings outstretched on columns of rising air, and the pond reflects it all in a luminous reverie that has never known stagnation. This is the spring that lives behind the black horse’s eyes. I am content to sit at the edge and toss thoughts like pebbles into its depths, watching the ripples expand in all directions. To the black horse, the human mind looks jagged, as if the roundness of experience has been cut up by ruthless lasers and most of it discarded in a great heap underground. Still, she embraces my saw-toothed ways, for in the mirror of her lake, they are no less beautiful than flowers blooming or vultures preening after a good meal.

(from The Black Horse Speaks)

What does it take to imagine the mind of a horse, let alone describe it to others? For me, it began with this unsettling exchange in the desert and the subsequent desire to immerse myself in the day-to-day activities of the herd. I didn’t merely observe behavior. I stepped over the line and allowed Rasa, Noche, and their pasture mates to influence me outside human agendas and thought patterns. I didn’t merely interpret what I saw. That would have given me a most limited view of the vast, multisensory insights horses exchange through empathic, shared awareness. My four-legged guides led me into a realm beyond words, and for months I could not articulate my discoveries. I had followed my horses so far into the place of silent knowledge that I was quite literally speechless when it came to describing why I was spending so much “idle time” with them. Still, the pressure of not being able to communicate these visceral realizations to others of my kind was almost unbearable. I felt like I was trying to carry water back to the tribe with nothing more than my own two hands. What I could grasp would never be enough, and most of it would slip through my fingers before I reached the campfire.

Then one day this deep well of awareness reached a boiling point on its own, its currents rising up from the base of my spine, surging through my gut, and flooding my heart where it was finally pumped up into my brain with such force that a series of strangely related, poetic notions spilled out for days with no effort at all. These metaphorical images, which I later collected in an unpublished book, The Black Horse Speaks, evoked a complex, nonverbal reality few of us two-legged creatures ever even notice, let alone master, mostly because we’ve become mesmerized by words. I understood at the most intimate level why Lao-tzu opened his famous Tao Te Ching with the caution, “The Tao that can be described is not the true Tao.” Yet like the elusive Chinese sage, I also felt compelled to give it my best try, no matter how futile it seemed. The phrases that initially poured into my computer were just as vague, paradoxical, and open to interpretation as the ones that dripped from Lao-tzu’s pen more than 2,500 years ago.

It was then, not quite so simply, a matter of finding other philosophical, psychological, and scientific theories that resonated with those metaphors. The final step is the words you see here, the act of compressing nonlinear intuitive and somatic experience into the linear thoughts we have come to value so highly, the style of processing and communicating information most people consider the most advanced form of intelligence on earth. It is in many ways similar to translating a multileveled, nuance-infused language like Chinese or Aramaic into English — only worse. Like the proverbial finger pointing to the moon, my only hope is that the following discussion will give those who work and play with horses a sense of direction in experiencing this unique perspective for themselves.

Researchers are trained to value objectivity. Scientists are not supposed to get involved with their subjects or be moved by them. Some people will undoubtedly dismiss anything new I have to say about horses when I admit that my theories are based on actually feeling something, anything, in their presence. Our culture denies the wisdom of the body and the senses, deifying the mind in a vacuum, training us to stand in production lines or sit in cubicles at computers and sublimate our physical and emotional needs in service to the cold, objective logic of consumerism and competition.

No wonder increasing numbers of people get their thrills vicariously, through films, romance novels, and Internet chat rooms, where their words and fantasies act as safe, sterile surrogates for the risks and rewards of actual human contact. We are afraid to feel as adults because we were repeatedly discouraged from feeling as children, and thus never learned how to manage our emotions. Our notions of human authority usually involve repressing authentic emotions in favor of those deemed socially acceptable — until the pressure builds, and true feelings explode all over the place. We commonly use food, alcohol, and drugs to medicate those unruly sensations into submission. In this way, people manage to put off the day of reckoning — and blame the inevitable breakdown on addiction rather than the deeply buried emotional messages behind it.

One of our culture’s most powerful and damaging myths is that the universe and every creature in it work according to predictable, mechanical laws. The resulting overemphasis on scientific validation leads to a certain ineptitude in the ephemeral realms of emotion, imagination, and intuition. If a phenomenon can’t be consistently and predictably measured or re-created in experiments, its existence is often denied. Anthropomorphism has become a deadly sin, not only in science but in society at large. We can hardly even anthropomorphize ourselves without threatening the system, for acknowledging the mercurial moods of body and soul challenges the very idea of clocking in from nine to five and churning out strategies, slogans, contracts, cogs, and widgets like robots programmed for one single purpose. Since the dawn of the industrial revolution, our society has promoted “mechanomorphism,” the inclination to see all living beings as machines. From the time of Descartes, much scientific inquiry has promoted describing everything from the body to the consciousness “generated within it” as mechanical phenomena.

In some circles, I’ve been accused of anthropomorphism, sentimentality, or just plain ignorance the moment I propose that riders and trainers cannot be truly effective without understanding how horses experience fear and anger, let alone sadness, depression, joy, and love. The head trainer at the breeding farm where I apprenticed was a woman well versed in the classical arts of dressage and jumping, yet she and I once got into a heated argument over whether or not horses have emotions. “It’s all instinct,” she insisted, “purely a survival mechanism.” She isn’t the only experienced equestrian who holds fast to the notion that horses are biological machines incapable of genuine thought or feeling. This is socially conditioned pseudoscience talking, myths that feed the human ego and justify all manner of neglect and abuse. A mechanism, after all, has no soul and hence no say in how it’s used.

The “Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness in Nonhuman Animals” set the record straight in 2012, proving that other species do in fact experience emotions and intentional behaviors. Yet change in the equestrian field and in animal husbandry is slow. Accepting that animals can think, feel, and make decisions is difficult for people who benefit from treating living beings as possessions, commodities and vehicles for ego gratification. Still, it’s important to remember that even close domesticated companions like dogs and cats do not always share our perspectives or priorities. I’m grateful that they often don’t, especially in the case of highly social, nonpredatory animals like horses who offer alternative approaches to power, collaboration, and “freedom through relationship,” lessons that lead receptive human beings to greater connection, compassion, and wellbeing.

In this respect, the term anthropomorphism is still useful as a cautionary concept. It’s important that we avoid indiscriminately ascribing human motivations to other species. We don’t assume that people in different cultures handle and interpret life’s challenges in the same way, or even that all residents of a small town share the same values.

Life is far more nuanced than we’d like to believe. My previous trainer’s assertion that emotionally motivated behaviors in horses are “just instinct,” and therefore evidence of lack of deep feeling and intelligence was flawed in its conclusions, for sure, but not completely inaccurate. As Webster’s defines it, “instinct,” is not necessarily the opposite of feeling at all: “1: a natural or inherent aptitude, impulse, or capacity 2 a: a largely inheritable and unalterable tendency by an organism to make a complex and specific response to environmental stimuli without involving reason and for the purpose of removing somatic tension b: behavior that is mediated by reactions below the conscious level.” It’s obvious that emotion has remained a primarily instinctual phenomenon in humans as well. Most people deny and sublimate their feelings, keeping them well below the conscious level until the somatic tension becomes so overpowering that the emotion overrides reason and finally expresses itself, often in violent and self-destructive ways.

In his book The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Carl Jung cites water as the most common symbol for the unconscious. The fact that water is also commonly associated with emotion in countless mythologies worldwide points to the fact that feeling has been recognized as a less-than-conscious phenomenon in human beings for eons. To the conscious mind, which Jung characterizes as “an affair of the cerebrum, which sees everything separately and in isolation,” feelings drag us down into an instinctual realm that, in our hubris, we believe is beneath us. The conscious mind knows spirit “only as something to be found in the heights. ‘Spirit’ always seems to come from above, while from below comes everything that is sordid and worthless.” Yet the clinical experiences described by Jung, Freud, and just about every significant analyst of the twentieth century have shown this obsession with all that is light and airy to be a form of escapism, “a refuge for all those timorous souls who do not want to become anything different.” The field of psychotherapy as a whole recognizes that a descent into the depths of emotion, as well as into the personal and the collective unconscious, always precedes the ascent into greater consciousness, transcendence, and lasting change. My experiences roaming through the mindscapes of silent knowledge taught me that water is a metaphor for psychological processes that are capable of reflecting the vast, nonlinear perceptions of all those things good and bad, creative and destructive, that have not yet become conscious.

Jung aptly describes the implications of this aquatic wisdom as it relates to the soul’s journey: “Whoever looks into the mirror of the water will see first of all his own face. The mirror does not flatter, it faithfully shows whatever looks into it; namely the face we never show to the world because we cover it with the persona, the mask of the actor. But the mirror lies behind the mask and shows the true face. This confrontation is the first test of courage on the inner way, a test sufficient to frighten off most people, for the meeting with ourselves belongs to the more unpleasant things that can be avoided so long as we can project everything negative into the environment. But if we are able to see our own shadow and can bear knowing about it, then a small part of the problem has already been solved.”

Every horse I had ever known was a reflecting pool for me. From the moment I laid eyes on my first horse Nakia (discussed in Chapter One), I felt intimately connected to her, as if we were resonating with the same unspoken truth, though I wasn’t prepared for the message behind our affinity. Somehow, this regal thoroughbred mare was able to mirror a host of unresolved issues, suppressed emotions, and unconscious attitudes I had not fully exorcised.

Though Nakia and I both refused to submit completely to the soul-demoralizing repression we had experienced, we were still influenced by the hidden scars of abuse, psychological wounds that revealed themselves in behavioral quirks and self-destructive outbursts challenging a system we felt powerless to change. She was held captive by a species that saw her as a possession, a beast of burden, a biological machine that loses its value if broken. Raised in a culture that emphasized predatory behavior, and forceful, coercive methods for maintaining power over others, I was held captive by my inability to imagine a more effective way of being. I had been the victim of a man’s efforts to control me through intimidation and criticism. Yet when sweet talk and bribery failed, I had no idea how to gain my horse’s cooperation without force and restraint.

Nakia and I both wanted things to be different, but our best intentions were stifled by the tyrannies of old habits. Tabula Rasa was to be my fresh start, my clean slate, an innocent filly with no baggage or past trauma to muddy our relationship. It didn’t take her long, however, to illustrate how profoundly handicapped I was in the world, not only in my sensory awareness but in how I remained blind to her true nature long after I thought I had evolved. Even with the painful insights Nakia provided, I continued to see Rasa through the haze of human conditioning that told me horses were lower life-forms, intellectual and emotional children in relation to their two-legged benefactors. In the beginning, I was able to understand her only superficially.

Still, there was no judgment involved. In its supreme equanimity, the lake behind the black horse’s eyes contained the healing waters of transformation, its fluid vision embracing flowers blooming, vultures preening, and my own jagged, self-indulgent thought processes. The spring-fed pond simply reflected what was, providing me with an oasis of clarity and peace in which to expand my awareness. The millisecond my behavior began to change, the reflection portrayed the more sensitive, empathic, creative person I was becoming, with no attachment to the past or projection into the future. Entering the rarefied reality my horses shared was like finding a watering hole in the desert.

Copyright 2023 by Linda Kohanov from the revised and expanded edition of The Tao of Equus, to be published in June 2024

Experience how horses lead people to greater physical, emotional, and spiritual balance in the upcoming four-day workshop The Tao of Equus 2023: Mindful, Authentic, Heart-Centered Wisdom for Personal Well Being and Professional Success (October 20 to 23). You can receive 20 percent off the tuition by contacting the Eponaquest Worldwide office at info@eponaquest.com. For a workshop description https://eponaquest.com/workshop/the-tao-of-equus-2023-mindful-authentic-heart-centered-wisdom-for-personal-well-being-and-professional-success-2/.

If you’re interested in the mythic, intuitive and mystical side of the horse-human bond, Linda is also offering 20 percent off her popular workshop Black Horse Wisdom (October 6 to 9). For a workshop description https://eponaquest.com/workshop/black-horse-wisdom-3/. Contact info@eponaquest.com to receive the tuition discount.

If you can’t attend an in-person, equine facilitated workshop this fall, Linda offers a series of self-paced, professionally produced online courses that offer innovative tools for emotional fitness, social intelligence, nervous system regulation, and balanced, connection focused leadership. These courses are also useful for equestrians and people who work with other animals. Go to her online course hub and scroll down the home page to see course descriptions at https://lindakohanov.com Use the coupon code 15rasa at checkout to receive 15% off tuition.

For a list of Eponaquest Instructors in your region: https://eponaquest.com/recommended-instructors/.