By Linda Kohanov

“Power and empathy are not mutually exclusive. Now more than ever, we need thoughtful, compassionate individuals to enter situations where suffering and conflict occur, and show a different form of strength, one that protects the vulnerable and holds people accountable without becoming contentious or abusive….”

I travel extensively, teaching leadership skills to business, community, and educational organizations. As the U.S. political climate became more vicious and divisive over the last year, increasing numbers of international clients offered me sanctuary.

“I will stay, regardless of who wins the election,” I always replied, flinching slightly as I considered the implications.

Time to face the stark reality of that seemingly simple pledge.

For me, “staying” means neither isolating myself from the ensuing drama, nor contributing to it. Staying involves witnessing the grief, despair, frustration, rage, and injustice both sides have been feeling for quite some time. It requires seeing people as individuals, rather than declaring one group “righteous” or “enlightened,” while objectifying the other as “stupid,” “brainwashed,” or “evil.”

Soon enough, staying will demand taking strong, thoughtful, nonviolent action to protect the vulnerable and explore new solutions. But sometimes, especially in the beginning, it will require standing with people who are disillusioned, frightened, and in pain when it appears there’s absolutely nothing we can do.

In this effort, I look to the very first President of the United States for guidance.

“Let your heart feel for the affliction and distress of everyone,” George Washington advised.

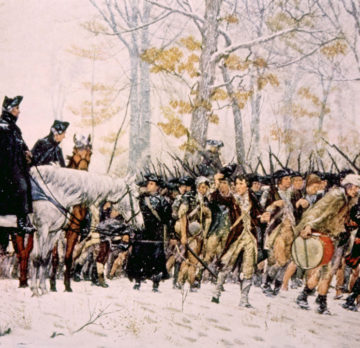

This was no small feat for a general who shivered with his troops and felt helpless as many of them starved to death at Valley Forge. Yet letters to trusted allies and friends reveal that he had been dealing with his own profound sensitivity for years, struggling to maintain composure in the midst of searing empathic responses to the settlers he encountered during the French and Indian War two decades earlier:

“I see their situation, know their danger, and participate in their sufferings without having it in my power to give them further relief than uncertain promises,” he wrote to his British superiors in 1756, asking for support. “The supplicating tears of the women and moving petitions from the men melt me into such deadly sorrow that I solemnly declare, if I know my own mind, I could offer myself a willing sacrifice to the butchering enemy, provided it would contribute to the people’s ease.”

Emotional Heroism

After the French and Indian War, Washington renewed himself in the pastoral embrace of his beloved Virginia farm. But rest and success did not make him complacent. As he repeatedly reentered public life, supporting one desperate cause after another, the turmoil he endured voluntarily was truly staggering.

Rather than shield his heart against the disappointment, anguish, and sheer horror he witnessed, General Washington remained steady and thoughtful in the midst of feelings that would have short-circuited the average person’s nervous system. His was not the coolness of the sociopath who feels no fear, but the authentic hard-won calmness of a man whose emotional heroism was so great that he was willing to accompany people into the depths of despair, and stay with them, offering hope through sheer presence.

As I pored over numerous books and colonial era documents, looking for clues to Washington’s extraordinary presence in the patterns of his actions, it struck me that his unique combination of fierceness, fairness, and compassion kept the troops together at Valley Forge, and beyond.

Washington’s open heart was not hardened by adversity, nor did it keep him from making tough decisions. He refused to coddle deserters or looters, ordering severe punishment for men caught stealing food. On rare occasions, he executed soldiers planning widespread revolt. And yet, he instituted a policy of humanity for prisoners of war, even as the British executed and tortured his own captured troops. In all of these efforts, he successfully kept large groups of people from lapsing into selfish, cynical, revenge seeking behavior.

A Vision of Strength and Hope

As the war progressed, the Commander in Chief increasingly rejected flamboyant, alpha-style dominance tactics in favor of a more thoughtful and compassionate approach, preferring to lead by example rather than intimidation. Though he wasn’t shy about pulling rank when necessary, his was a strong, steady, collected presence.

As the war progressed, the Commander in Chief increasingly rejected flamboyant, alpha-style dominance tactics in favor of a more thoughtful and compassionate approach, preferring to lead by example rather than intimidation. Though he wasn’t shy about pulling rank when necessary, his was a strong, steady, collected presence.

“I cannot describe the impression that the first sight of that great man had on me,” said one Frenchman. “I could not keep my eyes from that imposing countenance: grave yet not severe; affable without familiarity. Its predominant expression was calm dignity, through which you could trace the strong feelings of the patriot and discern the father as well as the commander of his soldiers.”

Washington conserved energy for true emergencies, refusing to create unnecessary stress, fear, or aggravation in others. Soldiers wrote home about his quiet confidence, dependability, consistency, and willingness not to use force.

Even during battle, the General radiated a centered yet still vigilant, purposeful strength. It radiated down into the horse he rode and outward to his troops, allowing people to borrow his remarkable courage in the most desperate circumstances.

As the British and their fierce allies, the Hessians, marched on Trenton, New Jersey, for instance, John Howland was one of a thousand troops assigned to delay the enemy’s advance across Assunpink Creek. “The bridge was narrow,” he wrote years later, “and our platoons were, in passing it, crowded into a dense and solid mass, in the rear of which the enemy were making their best efforts.”

Yet in that moment of utter confusion and desperation, Howland touched a vision of power, gaining, in the crush of battle, a sense of steadiness, renewal, and awe: “The noble horse of General Washington stood with his breast pressed close against the end of the west rail of the bridge, and the firm, composed, and majestic countenance of the General inspired confidence and assurance in a moment so important and critical. In this passage across the bridge, it was my fortune to be next the west rail, and arriving at the end of the bridge, I pressed against the shoulder of the General’s horse and in contact with the boot of the General. The horse stood firm as the rider, and seemed to understand that he was not to quit his post and station.”

Nonpredatory Power

As Ron Chernow reveals in his intricate biography Washington: A Life, the Revolutionary War hero was consciously evolving a style of leadership the likes of which the world had never seen, working tirelessly to educate and uplift his long-suffering soldiers, while dealing with constant assaults from a capricious, inexperienced, in-fighting Continental Congress, and a skeptical public at large.

As Ron Chernow reveals in his intricate biography Washington: A Life, the Revolutionary War hero was consciously evolving a style of leadership the likes of which the world had never seen, working tirelessly to educate and uplift his long-suffering soldiers, while dealing with constant assaults from a capricious, inexperienced, in-fighting Continental Congress, and a skeptical public at large.

Battling accusations that he was weak and indecisive by political enemies, he nonetheless stayed the course, eventually proving himself worthy of the public’s trust through the very act of valuing that trust to begin with. As Chernow observes:

Rejecting slash and burn, rape and pillage techniques that the British still used at times, Washington guarded against needless trauma perpetrated by and on friends and foes alike. During long stretches between battles, he also recognized the value of a feminine presence in camp to counteract the despair and disillusionment of an army stretched to the limit, enlisting the support of women, not as prostitutes, but as social activists capable of providing comfort, care and a host of other essential services to the soldiers.

Policy of Humanity

As the Revolutionary War intensified, King George ordered his officers to punish British soldiers and mercenaries if they showed mercy to surrendering revolutionaries. Most colonial soldiers were killed on the spot as a result, though some were tortured, starved, and mistreated aboard prison ships.

Washington’s troops, therefore, had good reason to exact revenge when the opportunity arose. Yet with each colonial victory came Washington’s demand to do the exact opposite. He not only spared the lives of a thousand Hessians captured during the Battle of Trenton, he literally marched them toward the promise of a new life.

“Treat them with humanity,” he wrote in orders handed down to all his officers, “and let them have no reason to Complain of our Copying the brutal example of the British Army in their treatment of our unfortunate brethren…. Provide everything necessary for them on the road.” Through this extraordinary, thoroughly unprecedented move, the General instilled tremendous self-control, and more than a hint of compassion, in his men.

Today, Washington is revered as the war hero who refused to be king. But his stunning ability to compel others to transcend deeply ingrained, seemingly justified, survivalist impulses stands out as even greater achievement, especially considering America’s current political climate—where some politicians stir up fear, purposefully activate the fight or flight response in constituents, and even advocate for an expanded use of torture at home and abroad.

In Washington’s own lifetime, however, Congress officially recognized the respectful treatment of enemy combatants as a strategic advantage that also exemplified the goals of the American Revolution. British leaders also recognized the negative effects of their own institutionalized cruelty. In 1778, Colonel Charles Stuart wrote to his father, the Earl of Bute: “Wherever our armies have marched, wherever they have encamped, every species of barbarity has been executed. We planted an irrevocable hatred wherever we went, which neither time nor measure will be able to eradicate.”

“In the end,” Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. observed in a 2005 Los Angeles Times editorial, “our founding fathers not only protected our national values, they defeated a militarily superior enemy. Indeed, it was their disciplined adherence to those values that helped them win a hopeless struggle against the best soldiers in Europe.

“In accordance with this proud American tradition, President Lincoln instituted the first formal code of conduct for the humane treatment of prisoners of war in 1863. Lincoln’s order forbade any form of torture or cruelty, and it became the model for the 1929 Geneva Convention. Dwight Eisenhower made a point to guarantee exemplary treatment to German POWs in World War II, and Gen. Douglas McArthur ordered application of the Geneva Convention during the Korean War, even though the U.S. was not yet a signatory. In the Vietnam War, the United States extended the convention’s protection to Viet Cong prisoners even though the law did not technically require it.”

The very fact that Kennedy had to write an article opposing torture in the 21st century shows how easy it is for people to slide back into old habits. But if scenes of American soldiers water-boarding suspected terrorists and humiliating naked Iraqi prisoners would have saddened Washington, recent acts of corporate greed would have inflamed him.

After all, when you consider that Washington fought the entire Revolutionary War as a volunteer — and I mean he literally did not collect a salary during the eight years he dodged artillery fire on horseback and begged for funds to feed and clothe his soldiers — well, you begin to understand how rarely the entrepreneurs and politicians who most profited from his efforts have bothered to follow his example.

Call to Action

If might always made right, and survival of the fittest depended solely on competition and brute force, American revolutionaries could never have defeated the British. As the grossly out-numbered colonial army ran out of guns, food, clothing, shoes, men, and finally, morale, it was Washington’s powerful yet empathetic, nonpredatory presence that repeatedly turned the tide, ultimately paving the way for a truly collaborative society of free men and women, one that we have yet to fully realize.

America’s first president was, and still is, a rare figure. In the intensely divisive wake of our 2016 election, the fierce compassion Washington extended to friends and enemies alike provides a remarkable contrast to the fear- and rage-enhancing, “attack-and-shame” strategies employed by far too many citizens, pundits, and political leaders.

Significant social change cannot take hold, let alone endure, until large numbers of sensitive, caring people become empowered. Now more than ever, we need thoughtful, compassionate individuals to enter situations where suffering and conflict proliferate, and, like George Washington, model a different form of strength, one that protects the vulnerable and holds people accountable without becoming contentious or abusive. Otherwise we will continue to see frustrated, disillusioned people acting out, bullies stirring up fear to gain control, and sociopaths callously thriving at others’ expense in business as well as politics.

Significant social change cannot take hold, let alone endure, until large numbers of sensitive, caring people become empowered. Now more than ever, we need thoughtful, compassionate individuals to enter situations where suffering and conflict proliferate, and, like George Washington, model a different form of strength, one that protects the vulnerable and holds people accountable without becoming contentious or abusive. Otherwise we will continue to see frustrated, disillusioned people acting out, bullies stirring up fear to gain control, and sociopaths callously thriving at others’ expense in business as well as politics.

Power and empathy are not mutually exclusive. Cultivating a balance between the two is essential for every responsible adult to achieve if we are finally to fulfill the promise of what our founders were ready to die for 1776.

In so many astonishing ways, George Washington was a revolutionary among revolutionaries. Two centuries later, we’re still grappling with the gift—and the burden—of freedom he so generously entrusted to the future. Rather than look for next remarkable leader to protect us from ourselves, it’s time for each and every one of us to dust off those stoic, faded images of the Father of Our Country and live the example he set before us. The coming months and years will give us plenty of practice.

This article was adapted from material first presented in Linda Kohanov’s 2013 book The Power of the Herd: A Nonpredatory Approach to Social Intelligence and Leadership. This book, along with her latest title The Five Roles of a Master Herder: A Revolutionary Approach to Socially Intelligent Leadership, offers insights into the history of leadership and power across multiple cultures, as well as innovative solutions for empowering people to collaborate and thrive in the context of freedom.

You can practice new ways to interact with others, lead, and handle conflict during two upcoming experiential workshops held in January and February 2017. In response to the recent events, Linda is offering significant discounts if you register by December 1st. The first workshop, Balance of Power: Leading Change in an Unpredictable World, is a powerful two-day introductory workshop taking place January 7 and 8. Linda shares compelling insights and practical tools from her 2016 book The Five Roles of a Master Herder. This innovative model—based on an ancient source of wisdom—offers a much-needed perspective on how free, empowered people can navigate continuously changing social and economic climates.

The second program scheduled for February 10-13, The Power of the Herd: Working with Eponaquest’s Horses to Master the Five Roles, is an in-depth workshop, where Linda combines tools from her two latest works, The Power of the Herd and The Five Roles of a Master Herder. Participants will receive copies of both books, and practice skills featured in each through a powerful combination of equine-facilitated learning activities and step-by-step processes that help people take these principles back to the human world. (All equine-facilitated activities take place on the ground, with horses who are specially trained for this work. No horse experience necessary.)

To read how businesses and individual participants have benefited from these workshops, see http://masterherder.com/endorsements/.

For more information about these programs or assistance in registering, contact the Eponaquest office at info@eponaquest.com or 520-455-5908.